The Loquacious Art

Graffiti is a loquacious art. Even better, we can swap the indefinite for the definite article and call it the loquacious art. It is the art of the blurt.

I’ve been thinking about that idea and the nature of graffiti more generally since finishing a post about a stencil I’d seen in a Bogota park. I used the post to riff on the stencil’s themes, but writing it got me thinking about graffiti as a medium, its properties and specificities.

The stencil that was the subject of the previous post. Picture property of the author.

Street art is visual but also intensely verbal. In some cases, it’s literally just words scrawled in public places. In others, it’s stylized depictions of words. Of course, it can and often does include visual depictions of all sorts. Regardless, graffiti is about saying something. It’s a conversational volley.

Spawn mural by the MHC crew (Bogota). Photo taken by the author.

Other styles of art do other things through other means, such as modify sound or craft narratives to trigger emotion, simulate experience, or generate immersive dream states (John Gardner’s “fictive dream”). Graffiti might also do some of those things, but it does them while being fundamentally dialogical. It’s chatty.

What is being said? On one level, street art is a chance to speak back to the city. It’s a vehicle for commentary. This social function of graffiti is what led Jello Biafra to suggest in a spoken word piece that subways and buses be covered in replaceable Kevlar to encourage people to write on the walls.

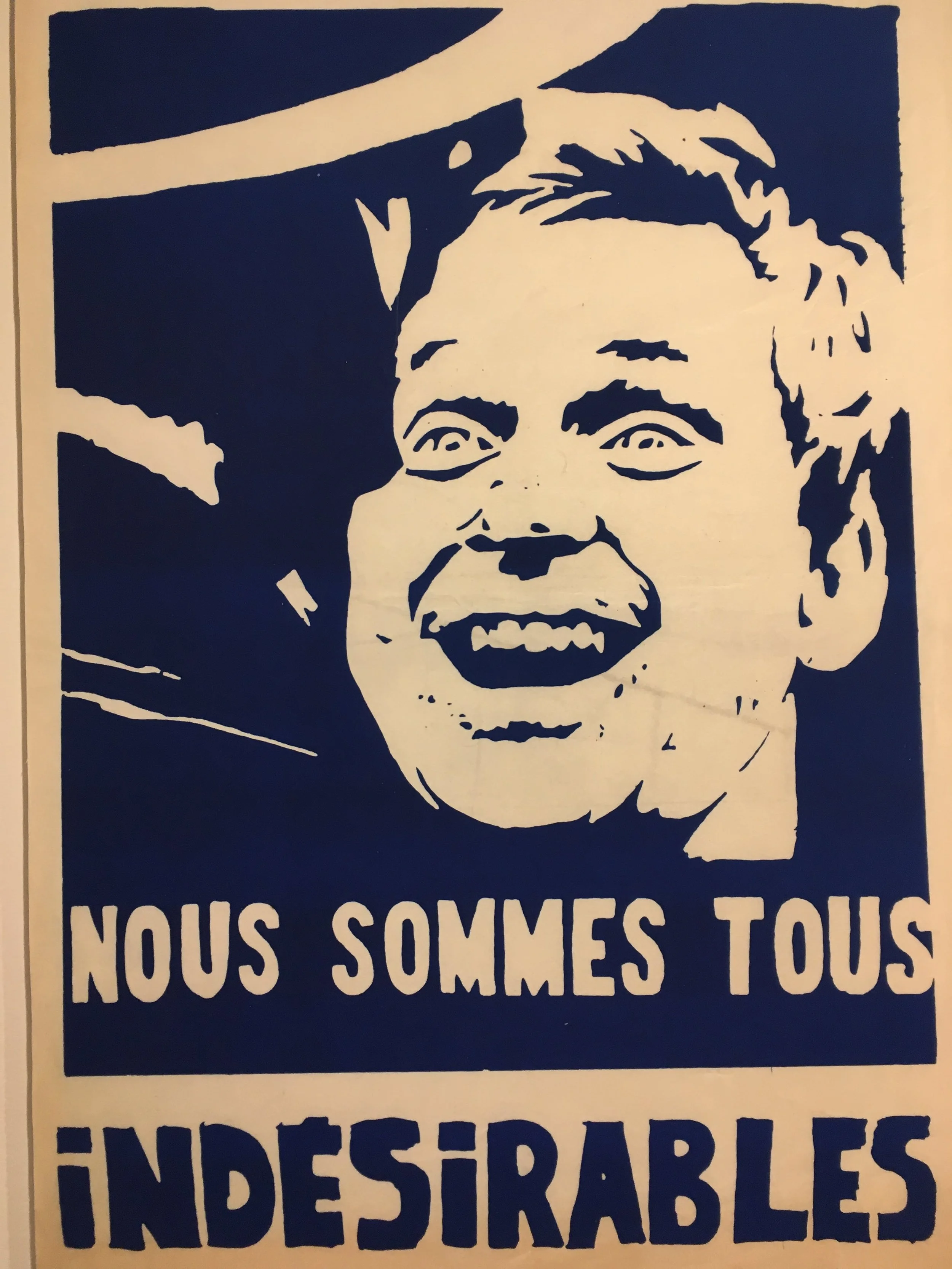

Original graffiti from the May ‘68 protests in France. Photo taken by the author at the Occupying Paris: May 1968 and the Spaces of Protest exhibit

In the case of the Cronenberg stencil, the comment is about the historical, geopolitical conditions that have shaped the world in which we find ourselves. As Burroughs said of the title Naked Lunch to which the stencil alludes, the naked lunch is the “frozen moment when everyone sees what is at the end of every fork.”

Street art might be speaking back, but who is it speaking to? A first answer follows from above: the generalized mass of the city, which is kind of everyone and kind of no one due to the spookily synergistic quality of human sociality. A second is people who get it. Often this is other graffiti writers and their complex culture of codes, shout outs, and crews. But that’s not always the case. The Cronenberg stencil, for instance, has the winking insider quality of pop art freakdom like They Live (1988) and is thus a nod to those in the know.

They Live (1988) stencil produced by some very talented artist (Boston). Photo property of the author.

Who is speaking? Graffiti is an inherently anonymous address. Part of this follows from the illicit nature of the medium. Even if you recognize or know the identity behind the author’s tag, it’s not publicly traceable. In that way, it has little in common with an op-ed signed by the author, though both are a way of chiming in and saying your piece.

The anonymized feature of graffiti’s address is what gives it the impression of being part of a conversation that is always already underway. At its best, this can give graffiti a generative, provocative quality. In his “Masked Philosopher” interview, Foucault famously said, “A name makes reading too easy.” Street art might be the medium of the masked social commentator.

“Wake up Punx” mural by Toxicomano (Bogota). Picture by the author.

To be human is to find oneself thrown into a world of things in general that are always already taking place. Perhaps, in that way, street art can be seen to give physical form to the conversations in which we wake to find ourselves always inevitably enmeshed.